Romanesque/gothic

- St Peter’s, Salford

- Crown & Kettle pub, Ancoats

- St Mary’s Church (the Little Gem)

- St Mary’s Parish Church Newton with Flowery Field

- John Rylands Library

- HMP Strangeways

- Whitworth Hall (University of Manchester)

- Manchester Town Hall

Medieval

- Chethams School of Music

- Baguely Hall, Wythenshawe

- Clayton Hall, Clayton

Manchester and surrounding areas blessed with a number of Romanesque and Gothic buildings. In addition to churches, also other buildings, for example, Strangeways prison, John Rylands Library, Whitworth Hall (University of Manchester), Manchester Museum, Crown and Kettle pub (originally possibly a courthouse?). Many buildings by Alfred Waterhouse and his son Paul (Manchester Town Hall, Strangeways prison, Whitworth Hall, Owens College) who favoured the high gothic/neo-gothic styles. St Peter’s, Ancoats is in the less common Romanesque style.

A small number of original medieval buildings survive, notably Baguley Hall, Baguley, Clayton Hall (moated), Clayton. Perhaps most famous is Chethams School of Music, dating back to the 1400s.

These large, imposing structures were often commissioned by wealthy philanthropists as grand gestures, indicative of conspicuous wealth, beneficence and bestowing of generosity to the poor (John Rylands, Chethams, Owens College, Manchester College). (This despite making their fortunes on the back of the poor upon whom they so ‘benevolently’ bestow their gifts!). Public bodies also commissioned large buildings such as town halls, market halls, baths and libraries.

Architects adopted styles as deemed appropriate to the wealth of the patron/commissioner, ornate, grandiose, full of detail. They demonstrated knowledge of architectural style. Waterhouse, for example, travelled extensively throughout Europe and no doubt studied and saw many styles during his travels.

ROMANESQUE/GOTHIC

St Mary’s Church (the Little Gem), Manchester – Weightman and Hadfield 1848

http://taking-stock.org.uk/Home/Dioceses/Diocese-of-Salford/Manchester-St-Mary-The-Hidden-Gem

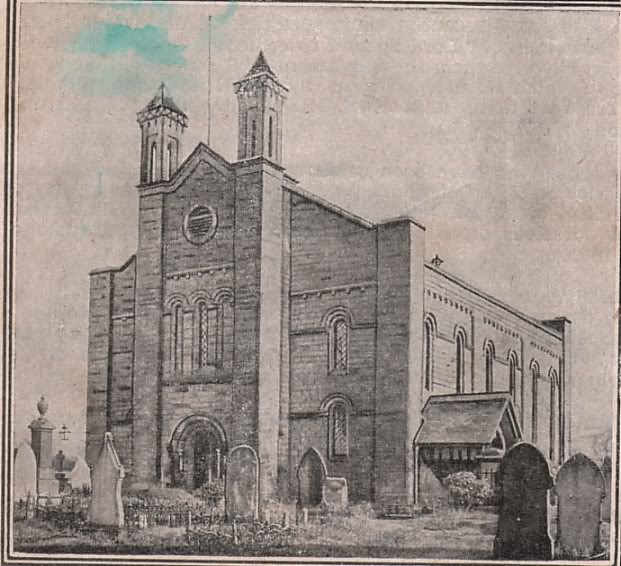

St Peter’s, Ancoats – Isaac Holden 1859

St Peter’s stands in the centre of the Ancoats Conservation Area, at the core of what is now known as the Ancoats Urban Village and is an important architectural and social landmark in East Manchester. It has a distinctive Romanesque style, with a basilica plan (a plain rectangle with side aisles marked out by columns and the transepts defined simply by a break in the roofline), an apsidal (semi-circular) chancel and a ‘campanile’ bell tower with fluted, pyramidal roof.

The Church was built in 1859 to designs by Isaac Holden, the founder chairman of the Manchester Society of Architects, who was able to design in a number of continental styles, and the building was consecrated in 1860.

https://www.heritageworks.co.uk/abpt-final/projects_peters.htm

St Mary’s Parish Church – Newton with Flowery Field – Haley and Brown, 1877

The thoughtful design is by Haley and Brown of Manchester and is of added architectural interest due to its Romanesque style rather than the Gothic style more commonly seen at that period. JM and H Taylor of Manchester added the West Tower and Turrets, the Chancel Organ loft, and Vestry in 1877, in a similar quality and sympathetic design, with the cost being funded by Public Subscription.

The main external feature, and prominent local landmark, the West Tower, with its two turrets, was the subject of a major restoration project in 2011, restoring the historic fabric to its former glory.

The following extract was taken from the English Heritage listing:

Church of 1840 for the Church Commissioners by Hayley and Brown of Manchester, with chancel of 1877 by J. M. and H. Taylor of Manchester. Built in an Italian Romanesque style

This mid C19 Commissioners’ church is a thoughtful design by Hayley and Brown of Manchester of added architectural interest due to its Romanesque style, rather than the Gothic which was more commonly used for these buildings.

http://www.stmarysnewton.org.uk/history/

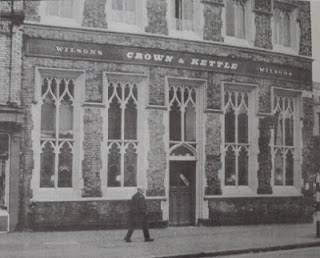

Crown and Kettle pub, Manchester (former courthouse?)

From the schedule of listed buildings

‘Public house. Probably earlier C19, altered. Buff brick with

stone dressings, hipped slate roof. Square plan on corner

site. Two storeys, 5×5 bays; very tall transomed 2-light

windows to ground floor with Gothick tracery and linked

hoodmoulds, a doorway in the lower part of that in the centre

of the Oldham Street facade, with 4-centred arched fanlight,

and similar doorways in the 2nd and 5th bays of the Great

Ancoats Street facade; shorter 2-light windows to 1st floor

with cusped lights, also with linked hoodmoulds. Interior:

unusual ceiling with very large Gothic pendents; small snug

with mahogany panelling said from airship R.101. History: said

to have been used as courtroom associated with former market

close to this site.’

‘the Crown & Kettle, still extant at the corner of Great Ancoats Street and Oldham Road, and first mentioned in the 1800 directory 11. This pub had the distinct trade advantage of overlooking New Cross, an important meeting point for traders, travellers and carriers, as well as a ‘rendezvous where all kinds of opinions could be ventilated: politics, socialism, religion, literature and multitudinous other subjects’ 12

11Neil Richardson,‘The Old Pubs of Ancoats’, p4

12Manchester City News. Memories of New Cross, 2.10.1920

https://bandonthewall.org/history/19th-century-history/chapter-1-an-eventful-century/more-seriously/

‘A pub has stood at this location since 1734 (previously as the Iron Dish & Cob of Coal [1]) but it closed down in 1989 following trouble between Manchester City and United fans.’

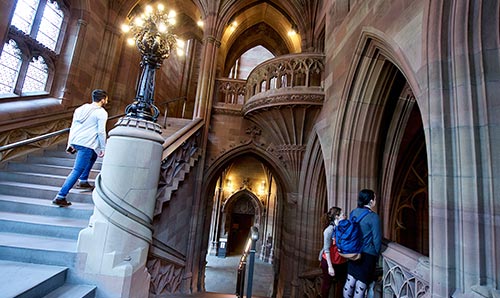

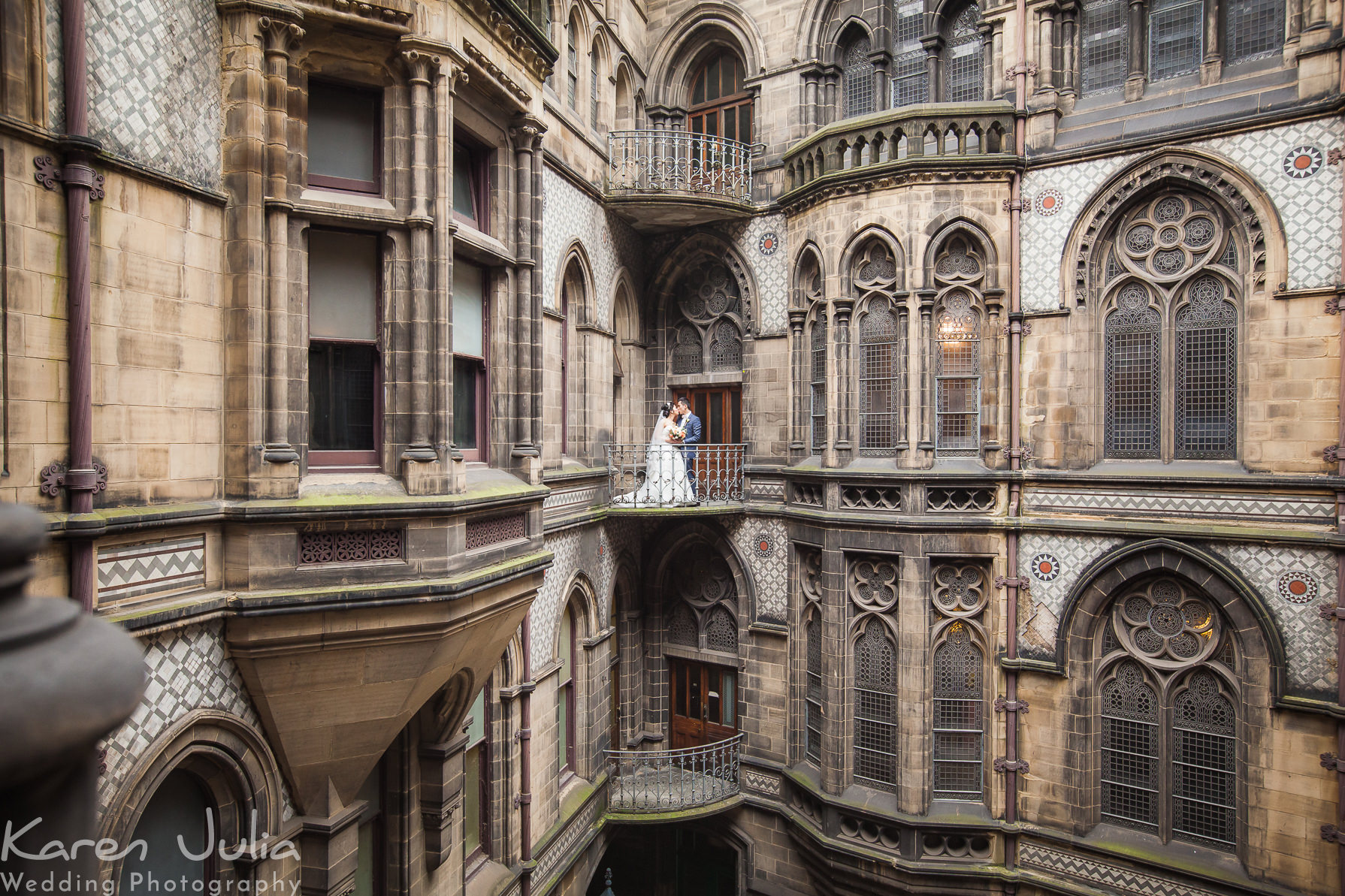

John Rylands Library – Basil Champneys 1900

‘The John Rylands Library is a late-Victorian neo-Gothic building on Deansgate in Manchester, England. The library, which opened to the public in 1900, was founded by Enriqueta Augustina Rylands in memory of her husband, John Rylands.[4]

‘The library has a crypt above which the building has two unequal storeys giving the impression of three. The ornate Deansgate facade has an embattled parapet with open-work arcading under which is a central three-bay entrance resembling a monastery gatehouse. Its two-centred arched portal has doorways separated by a trumeau and tall windows on either side. Above the doors are a pair of small canted oriel windows. Surfaces are decorated with lacy blind tracery and finely-detailed carving.[13] The carving includes the “J. R.” monogram, the arms of Rylands, the arms of Rylands’ native town, St Helens, and those of five English, two Scottish and two Irish universities and those of Owens College.[25] On either side of the entrance portal are square two-storey two-bay wings with plain walls with a string course containing grotesques and large octagonal lanterns. Behind the entrance portal flanked by square towers is the three-light east window of the reading hall. It has reticulated tracery and shafts in a similar style to the parapet. In front of the library are Art Nouveau bronze railings with central double gates and lamp standards.[13]’

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Rylands_Library

HMP Strangeways – Alfred Waterhouse 1868

French Gothic gatehouse entrance

Whitworth Hall, University of Manchester – Paul Waterhouse, 1902

Manchester Town Hall – Alfred Waterhouse 1877

- Aerial photograph of the UK by Webb Aviation (0044) 0161 439 5197 m0776 9688748

MEDIEVAL

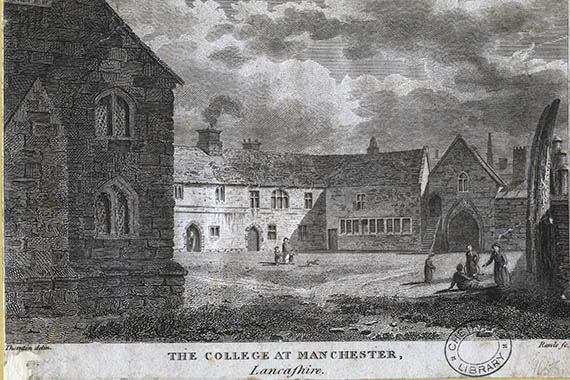

Chethams School of Music

‘The buildings which continue to house Chetham’s Library and the Baronial Hall were built from 1421, on the site of the manor house of Manchester, as a college for priests connected to the neighbouring Manchester Cathedral. They survived through the religious tumult of the Tudor era and the experiments of its 16th century warden, Dr John Dee. A prominent burn mark on a table in Dee’s office is, it is said, the footprint of the devil, summoned by the alchemist in his lifelong pursuit of knowledge. Through the English Civil War, the college’s position on a bluff above the join of the rivers Irk and Irwell made it a key defensive asset. Afterwards, disused, damaged by gunpowder and reportedly home to free-ranging pigs, the buildings were acquired by the executors of Humphrey Chetham, twice the High Sheriff of Manchester, through his will of 1653. This stipulated the establishment of a free public Library, ‘for the use of schollars and others well affected’, and a School for the education of forty poor boys from honest families.’

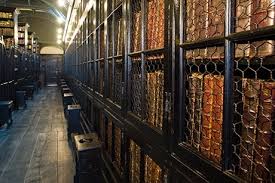

‘Chetham’s Library, which was founded in 1653, is the oldest surviving public library in Britain. It was established under the will of Humphrey Chetham (1580-1653), a prosperous Manchester textile merchant, banker and landowner. Chetham also made provision for a school for forty poor boys, now a specialist music school of world renown, and for five chained libraries to be placed in local churches.

The building that houses Chetham’s is even older than the foundation of the School and Library. It was built in 1421 to accommodate a college of priests and remains one of the most complete medieval complexes to survive in the north west of England. The beautiful old sandstone buildings, together with the magnificent Library interior, create a unique atmosphere for readers and visitors alike.

At the time of the Library’s foundation, there was no facility for independent study in the north of England. The twenty four feoffees, or governors, appointed by Humphrey Chetham, set out to acquire a major collection of books and manuscripts that would cover the whole range of available knowledge and would rival the college libraries of Oxford and Cambridge. Today the Library continues to expand its collection and now specialises in the history and topography of Greater Manchester and Lancashire, holding material on a wide range of local subject matter.

Humphrey Chetham’s will of 1651 stipulated that the Library should be ‘for the use of schollars and others well affected’, and instructed the librarian ‘to require nothing of any man that cometh into the library’. Chetham’s has been in continuous use as a free public library for over 350 years, and the strength and breadth of the collections, coupled with its rich history, ensures that Chetham’s continues to be both a significant centre for study and research and a deservedly popular tourist destination.

Chetham’s is built on a sandstone outcrop at the confluence of the Rivers Irwell and Irk, a site of strategic importance which has been occupied since Roman times. The present building dates from the second quarter of the fifteenth century. In 1421 Thomas de la Warre, Lord of Manchester and rector of the parish church, obtained a licence from Henry V to re-found the church as a collegiate body, with a warden, eight fellows, four clerks and six lay choristers.

De la Warre gave up his own manor house and land for the impressive new building, which was built of local sandstone, quarried in Collyhurst and brought to the site by river barge. The generous accommodation included a large hall, the warden’s own lodgings and a set of rooms for each of the fellows. In addition, the complex had its own bakehouse, brewery and stables, as well as ample domestic facilities and guest rooms. Other than the church it was the largest building in the medieval town of Manchester.

The survival of such a complete medieval domestic building is rare in itself, and its troubled history makes that survival all the more surprising. In 1547 the College was dissolved and the Stanley family acquired the property as a town residence. The College was re-founded, closed down and re-opened, but gradually fell into a state of disrepair until its triumphant resurrection as the vessel for Humphrey Chetham’s glorious legacy.’

http://library.chethams.com/about/history/the-medieval-buildings/