Ancient mythological depictions are complex. They may be regarded as a means of making sense of the elements or occurrences that today may be explained by science (Apollo the sun god, Poseidon, god of the ocean). They may also represent versions of real events, sometimes elaborated upon, altered and embellished. Mythological art is also a visual depiction of the oral tradition of passing on stories, information, news and beliefs. Myths do not necessarily carry any moral meaning or teaching but could be simply illustrations of stories that would otherwise be passed on through the telling. However, they were, at different stages in social history, interpreted as having deeper, moral meanings and messages for humankind – how to live a virtuous life, how to avoid ‘sin’, the perils of excess etc.

One such example is the story of Pandora. A long-lasting mythology that appears in many media, ceramics, sculpture, paintings, film, comics, music. The concept of Pandora’s box (or, more correctly vessel) releasing unbridled evil into the world has become synonymous with any irremediable act, disaster, event or undesirable outcome. Mitigated only by the belief that (in some versions of the mythos) Hope remained in the vessel, Pandora is variously treated as a version of Eve, a temptress, seductress, an unfortunate ‘holder’ of the vessel, an innocent creature moulded from clay.

Mythology is fluid with some myths taking on more varied forms than others and changing over time and depending on the audience.

Researching the various mythologies and imagery surrounding Pandora the following were the most strikingly apposite to me and so the most interesting.

Pandora

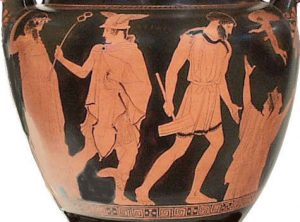

Goddess of beneficence – all-giver, or all-gifted since she was said to have been endowed with skills and graces by the gods. The version given by the poet Hesiod has her conveying a pot (not a box as in post-antique art) of ills for mankind (her husband-to-be is Epimetheus) and releasing them, withholding only Hope. This is not a subject for ancient art. She was worshipped in Athens more as purveyor of skills for mankind from the gods. She is shown rising from the ground, or being dressed by Athena and Hephaistos (and other gods, on the base of the Athena Parthenos).

Birth of Pandora. Detail from Attic red-figure clay vase, about 475-425 BC. Oxford. Ashmolean Museum G275. Photo. Beazley Archive © Beazley Archive, Ian Hiley

http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/dictionary/Dict/ASP/dictionarybody.asp?name=Pandora

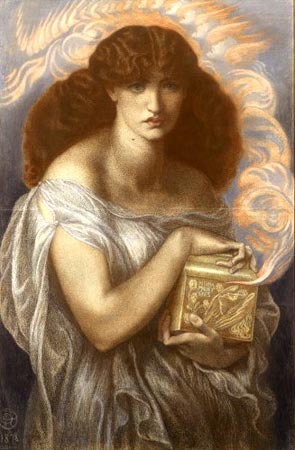

Pandora – Gabriel Dante Rossetti 1878

Rossetti’s Pandora (he painted two such paintings) depicts a woman with a passive, almost sullen expression. The infamous box (Rossetti chooses the box imagery rather than the vessel) is held in long, sinewy fingers. It is hard to discern whether Pandora is holding the box closed or about to open it. Her expression gives nothing away, her gaze almost defying the viewer to make their own decision. However, a plume of smoke, presumably the ills and evils of the myth, curls around her, over the shoulder and into the distance behind her. She is impassive and appears oblivious to, or unconcerned by, its escape.

There is no evident emotion in this painting, neither remorse nor relish at the unleashing of evil into the world. From this I would view the subject as simply that, an interpretation of a popular subject, particularly given that the sitter is Rossetti’s muse, Jane Morris. Perhaps she is his Pandora, his temptress, his Eve? Is she defiant or delinquent?

In terms of subject matter, many rich Victorians would have been making the ‘Grand Tour’ at this time. As a result Greek and Roman artefacts were popular among collectors, museums were filling with Greek and Roman sculpture, pottery, architecture. Thus, this subject matter would be typical of the time and was also employed by other artists such as Alma-Tadema and Waterhouse.

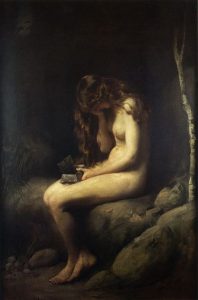

Thomas Kennington (British, 1856-1916), Pandora, 1908

Although painting around the same time as Rossetti, this study by Kennington takes an entirely different approach. Kennington’s Pandora is naked, full of remorse, vulnerable. Dark and brooding, a young Pandora sits with head bowed on her hand, the other hand holding the patently empty box (again rather than the vessel). No suggestion of mischief, defiance or evil, simply the epitome of despair.

Kennington was known for his realism and true to life portrayal of the everyday. Perhaps his vision of Pandora was only that of the evils unleashed on mankind as he saw on the streets every day? Perhaps he saw little hope in his subjects and so to him, Pandora represented only the negative, hope being absent?

Other artists explored:

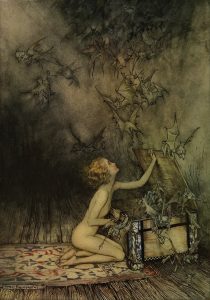

Arthur Rackham – Pandora

http://www.bpib.com/illustrat/rackham.htm

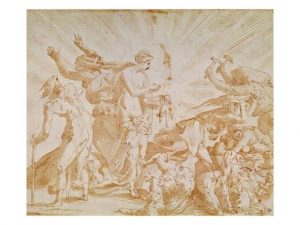

Pandora Opening the Box – Rosso Fiorentino – 1494-1540

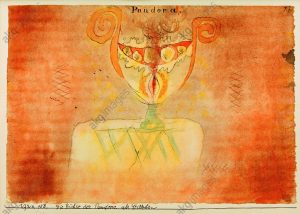

Paul Klee – Pandora’s box as a still life 1920

https://newrepublic.com/article/85977/pandora-box-japan-nuclear-fukushima

Pandora – William Adolphe Bouguereau 1890

Pandora’s box is an artifact in Greek mythology, taken from the myth of Pandora’s creation in Hesiod’s Works and Days. The “box” was actually a large jar given to Pandora (“all-gifted”, “all-giving”) which contained all the evils of the world.

Today the phrase “to open Pandora’s box” means to perform an action that may seem small or innocent, but that turns out to have severe and far-reaching consequences.

——————————-

“William Bouguereau is unquestionably one of history’s greatest artistic geniuses. Yet in the past century, his reputation and unparalleled accomplishments have undergone a libelous, dishonest, relentless and systematic assault of immense proportions. His name was stricken from most history texts and when included it was only to blindly, degrade and disparage him and his work. Yet, as we shall see, it was he who single handedly opened the French academies to women, and it was he who was arguably the greatest painter of the human figure in all of art history. His figures come to life like no previous artist has ever before or ever since achieved. He wasn’t just the best ever at painting human anatomy, more importantly he captured the tender and subtlest nuances of personality and mood. Bouguereau caught the very souls and spirits of his subjects much like Rembrandt. Rembrandt is said to have captured the soul of age. Bouguereau captured the soul of youth.

Considering his consummate level of skill and craft, and the fact that the great preponderance of his works are life-size, it is one of the largest bodies of work ever produced by any artist. Add to that the fact that fully half of these paintings are great masterpieces, and we have the picture of an artist who belongs like Michelangelo, Rembrandt and Carravaggio, in the top ranks of only a handful of masters in the entire history of western art.

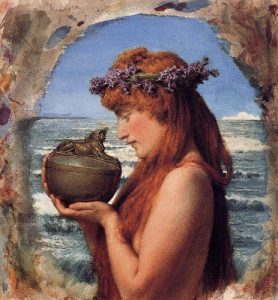

Pandora – Alma Tadema 1881

Pandora – Waterhouse 1898

http://fannycornforth.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/the-cruelty-of-hope.html

Pandora – Armando Adrian-lopez 2017

Armando Adrian-Lopez combines the representational with the symbolic to form images that are readily understood and that focus on the magic present in everyday life. The visual meanings inherent in his work are multi-layered, narrative, and dream-like.

May my work inspire you to delve deep into your psyche, emotions, consciousness, and the innate magic of life.

Pandora – Mujeres Al Borde Collection – oil on canvas – 20″ x 34″ by Armando Adrian-Lopez, a visionary Mexican artist , Abiquiu, NM completed 2017

Additional research notes:

Pandora 1878

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

In the Greek myth, the god Jupiter gave a casket to Pandora, a mortal woman, and forbade her from opening it. She took it back to earth and opened it, letting forth all evils into the world. Only Hope was left inside. The Latin words on the casket, ‘Ultima Manet Specs’ mean ‘Hope remains last.’ The face and figure type of Pandora are based on Jane Morris but this is not a portrait.

The meaning of the image is ambiguous. Is Pandora an evil femme fatale who ruins men by her disobedience? Or is she a heroic woman who defies the gods to take control of her own fate?

http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/ladylever/exhibitions/drawings/women/pandora.aspx

Thomas Kennington (British, 1856-1916), Pandora, 1908, oil on canvas, signed and dated lower left, 80 ½” x 56 ½”

Kennington attended several prestigious schools, including the Academy Julian, where he trained alongside Bouguereau. Exhibiting frequently at the Royal Academy, he became a respected portrait artist, painting Queen Victoria in 1898. Passionate about social reform, he established an independent institution that provided exhibition opportunities for artists rejected and discouraged by the dictatorial Academy. Pandora is a compelling portrait of human suffering, an allegory for the looming catastrophe ‐ humanity at the brink of a modern age. It is interesting to note that at the height of Academic painting, nudes were only permissible in the form of mythological beings, with genitalia hidden from view.

http://www.theknohlcollection.com/portfolio/detail/pandora/